As Larry Bird shot over Julius Erving in 1984, this reporter had the ideal courtside view at Boston Garden./Photo by Dick Raphael

It would be negligent to present a series of NBA flashbacks to the Michael Jordan era without including an article about Boston’s superhero, Larry Bird.

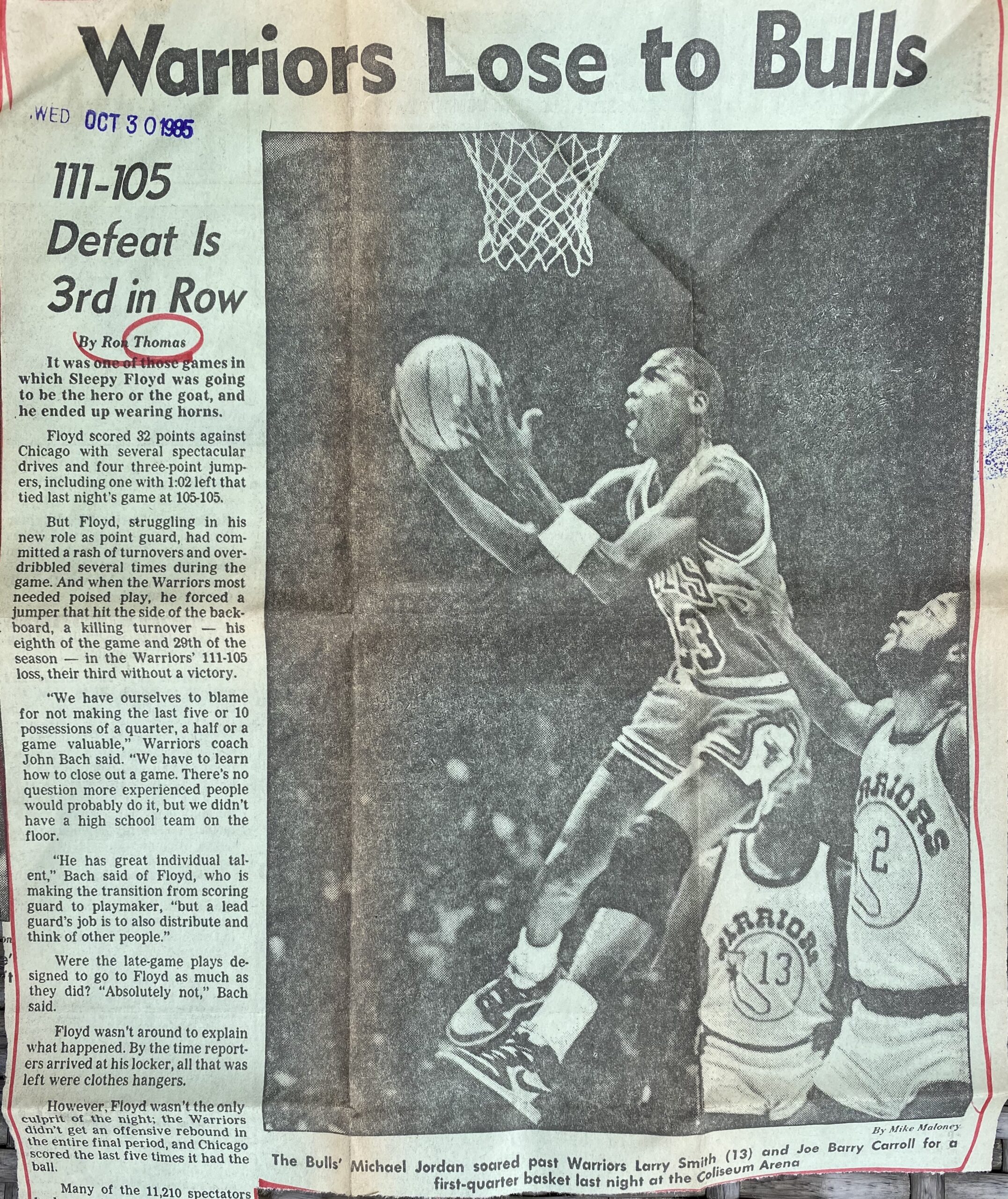

The Celtics’ “Larry Legend” gave me and another reporter, Marty McNeal, one of the best interviews of our careers. The 1985-86 Celtics had come to Oakland to face the Golden State Warriors, and Bird agreed to talk to us after practice. To our amazement, no other reporters had requested Bird, so when he walked onto the court Marty and I had him to ourselves.

He came into the NBA in 1979 as a very reluctant talker, but seven years later Bird had become what reporters call “a good quote.” He usually was affable and could crack a funny line, and that day Bird was in an unusually talkative mood. Marty and I kept feeding him questions and he answered with an openness and ease we hadn’t expected.

When the interview ended, I had enough quotes to write a two-part series. My favorite segment was about when Bird first felt a passion for basketball, so I hope you enjoy reading his sharp memories of that event in my Feb. 20, 1986, San Francisco Chronicle article “How Bird Took Off.” That night, he crushed the Warriors with 36 points, 12 rebounds and 11 assists.

This article also serves as my tribute to Marty McNeal, who died on May 21st. He was one of the funniest people you could ever meet, which I’m sure was one reason Bird tolerated us for so long.

This will be the last segment in my series about the roots of NBA superstars from the Michael Jordan era. The research and writing involved reminded me of how exciting it was to cover the NBA when it was just starting its climb toward worldwide recognition. I appreciate all of you who have read my articles. If you have enjoyed venturing into pro basketball’s past, I encourage you to buy my book, “They Cleared the Lane: the NBA’s Black Pioneers” from Amazon or University of Nebraska Press.

How Bird Took Off

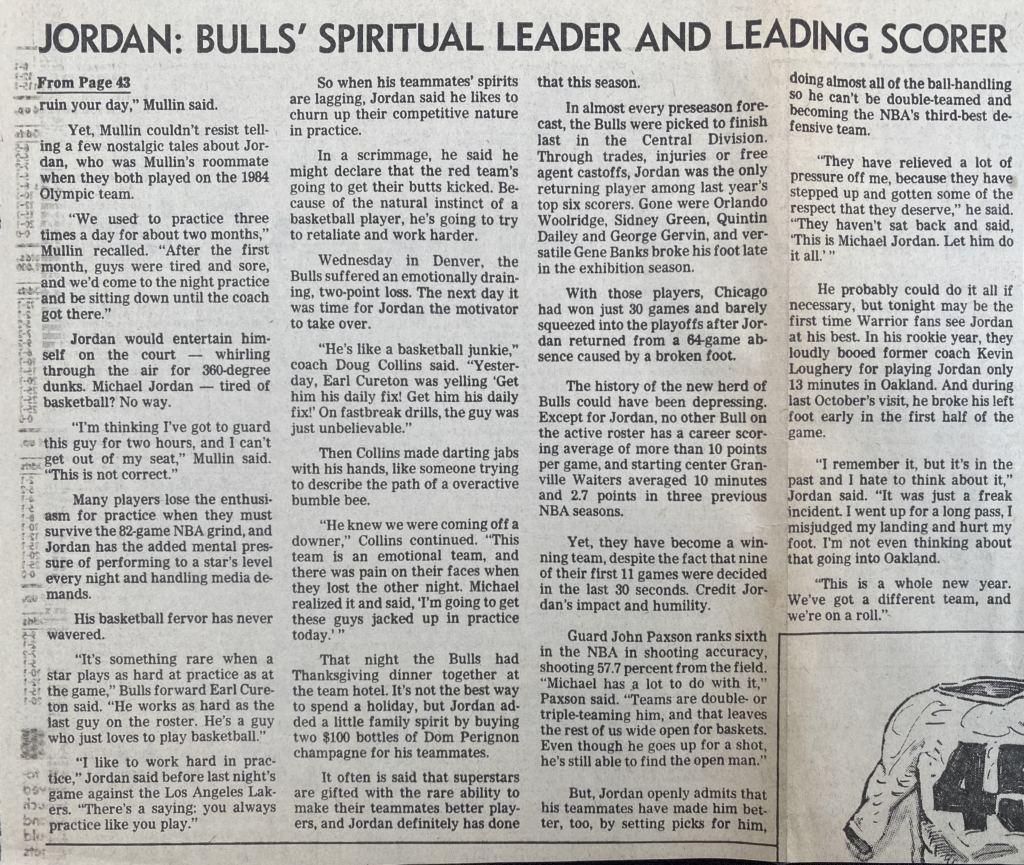

By Ron Thomas

Everybody remembers the first time he fell in love, and Larry Bird is no exception. The circumstances are a bit different, though. For Bird, it was the day he realized he could sink a jump shot at will.

“I can remember when I started hitting a lot of shots,” Bird said a few days ago. “I was shooting around, and all of a sudden shots started going in. I can remember to this day when that happened.”

In French Lick, Ind., where Bird was raised, he always liked basketball. But he didn’t begin to love it until that day, at the age of 14.

“I was at my friend’s house and there were people there and everybody was sitting around,” Bird said. “We started to shoot until somebody missed, and I hit 10 or 12 in a row.”

Everybody noticed his accuracy.

“Then I started concentrating on it and liking it. All of a sudden you feel excited about it and start playing ball all the time. That’s exactly what happened to me.”

A fortunate injury

About two years later, another fluke infatuation made Bird embrace passing as a skill. He was playing for Spring Valley High.

“In practice one time, I had just come back from a broken ankle and I really wasn’t quick enough or able to jump to get a shot off,” Bird recalled.

“I just started passing the basketball, and it seemed like everybody started getting excited about it. Next thing I knew, I was labeled a pretty good passer.”

Bird’s high school coach, Jim Jones, taught him the fundamentals. “Once I got them, the game came pretty easy.”

When the older players in his neighborhood started choosing him first in pickup games, Bird knew he had a special affinity for the game. He hasn’t lost it.

At Indiana State, Bird averaged 30 points a game and led the Sycamores to the 1979 NCAA finals, where they lost to Michigan State and Magic Johnson.

A new beginning awaited Bird in Boston. As a rookie, he averaged 21 points and five assists, and the Celtics leaped from 29 victories the previous season to 61 under demanding new coach Bill Fitch.

“He was the best thing that could have happened to me,” Bird said. “He made me a great player in a short period of time, because he had restrictions on me. Plus, after he found out I could do certain things and started trusting me, he let me go. All I had to do was give him eye contact, and he’d run my play.”

Three years later, however, Fitch’s players had grown to despise him because of his fanaticism. After Milwaukee swept the Celtics in the 1983 playoffs, Fitch resigned before his players could mutiny.

Saved by team defense

“Bill Fitch wasn’t really mean,” Bird said about the current coach of the Houston Rockets. “He was a winner. He’s not going to let himself get beat because he was not prepared. That’s one thing a lot of guys could not understand, and I could understand it.”

But Bird also understood that his teammates couldn’t tolerate Fitch’s pressure cooker. “I think Bill Fitch got out at the right time,” Bird said.

Now Bird plays for K.C. Jones – “the greatest human being I’ve ever been associated with” – and has teammates who share Bird’s ability to excel in the game’s subtleties. Especially on defense.

“You’ve got to know your teammates real well, because if you make a move on the defensive end, somebody’s got to cover up for you,” said Bird, who ranks eight in the NBA in steals with 2.2 per game.

Bird’s need to play with a team concept was painfully obvious in this month’s All-Star Game. He is neither a great leaper nor is he exceptionally quick – and it showed.

Small forwards like James Worthy jetted past Bird. Big forwards like Ralph Sampson powered over him as if he were Spud Webb without his launching pad.

But bring Bird back home to his Celtics, and he’s on the NBA All-Defensive second team again, as he has been for the past three years.

“Playing with these players has been the easiest part and made my game mature,” he said. “Dennis Johnson is the best player I ever played with. He knows what I’m going to do out there, and I know what he’s trying to do. It makes it very easy. Bill Walton’s getting to be the same way.”

Walton joined Boston this season after six years with the pathetic Clippers’ franchise. It took Bird awhile to figure out Walton’s game, but he has helped Walton become Boston’s leader in blocked shots per minute.

Plotting with Walton

Late in the fourth quarter of Sunday’s victory over the champion Los Angeles Lakers, Walton rose like a monster from the deep to crush a Worthy jump shot.

Worthy didn’t know it, but he was “set up” by Bird. Walton was the hit-man.

“Bill always tells me to set him up a couple times so he can block the shot,” Bird said. “My man will come driving in there and I’ll cut right in front of him so when he jumps, he can’t stretch all the way out.”

That’s what Bird did to Worthy, who shot anyway. “Then Bill will smack it,” Bird said.

Bird doesn’t block many shots, only 34 in 51 games this season. But he blocks a lot of paths to the basket.

“A lot of guys are rhythm shooters,” he said. “If you just get your feet in the way – where maybe they have to take a little jab step and then go up – they’re off balance a little bit.

It even throws off Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s sky hook.

“What I do is very minor,” Bird said. But if it were minor, he would have played on a losing team by now. He never has.

Even great players usually aren’t that fortunate. Just look at Walton’s purgatory with the Clippers.

But now, as a Celtic, “watch how he enjoys himself,” Bird said. “Talk to his wife and she says, ‘This is unbelievable. Bill’s talking to me now. He hasn’t talked to me in four years.’

“He’s been through it, and I don’t want to go through it.”